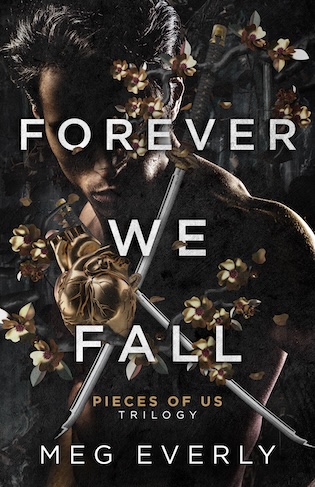

Forever We Fall: A Dark MM Romance

Meg Everly

(Pieces of Us, #2)

Publication date: November 26th 2024

Genres: Adult, Contemporary, Dark Romance, LGBTQ+, Romance

A love worth dying for.

Hotaru Kido

Leaving Japan was bad. Leaving sh*tty London is worse. Why? My destination. Willoughby Ridge Boarding School.

It smells as old as it is. No one can find the place on a map. And it’s boys only. Did you hear that last bit? No. F*cking. Girls.

Even the teachers. Male. The only pair of t*ts for kilometers belong to the headmaster’s hot little secretary. That’s why I got myself in trouble and am sitting in the office when he walks in.

This guy is new. He’s gaunt and terrified of the big man behind him. No one seems to notice the wince when he sits or the way he catalogs the guy’s every move. I do.

If I’d stayed in class that day, my life would have been a billion times easier. If given the chance, would I have chosen to keep it simple or put myself between him and his tormentor?

Arlo Judge

When your parents and brother die in a freak accident, you certainly think that’s the worst that could happen. It’s not. I’ve seen the depth of h*ll. Felt the burn. Lived the agony.

When I’m deposited in the middle of nowhere boarding school, I’m relieved for the first time in a long time. Only my suitemate sees too much. He gives me hope when I know there is none.

In him, I find comfort and friendship that can’t last. My tormentor won’t allow it.

With his care and kindness, I see a way out. I have to finish my journey through h*ll to get there. I don’t know what will be left of me, of us, when I get to the other side.

—

EXCERPT:

“To the headmaster’s office.”

“Thank you.” I stand and reach for my bag.

“Thank you?” he scoffs. “Why on earth are you thanking me for that?”

One day, he’ll learn not to speak to me in front of the class. If he has any semblance of a brain, it’ll be today.

I sling my bag over my shoulder and head for the door. When I’m on his level and standing several inches taller than him, I grin.

“It will give us, Bridgeport and me, a chance to discuss your subpar teaching skills and your nightly visits to a certain student’s room.” The class gasps. “Plus, the headmaster’s office has to be more interesting than this class.”

Before he can formulate a response, I’m out the door and headed for the main office. The classroom erupts into chaos behind me.

I’m smiling for the first time since I arrived at this awful place.

Have I actually seen him visiting another student’s room? No. But he doesn’t know that. And I like to fuck with people. They’re pretty easy to manipulate. I don’t know why, but people always have been. Easy to read. Easy to influence. Puppets, most of them.

No one is in the hallways. All the tenth through thirteenth years are in class. They separate us from the first through fifth, sixth through ninth, and then the rest of us. I haven’t seen the whole school come together, but I heard they do for the beginning and end of the year celebrations.

Can’t wait.

I exit our building, head across campus, and shove through the main office entrance. The place is bustling. A lady behind the desk is on the phone. Or should I say the lady, as in the only one? I sit in the waiting area, put my backpack on the chair beside me, and drink her in.

Blond hair pulled back at the nape. Glasses sit on the bridge of her nose. A cardigan hugs her shoulders and meets with little buttons at the center of her chest. Her breasts aren’t large, but they’re the biggest in these parts. They’re big enough to fill my mouth and tempt my tongue.

She clocks me and automatically gives me the hold-on-a-minute finger. Then her gaze meets mine.

Her pink lips part. Her throat works on a big swallow. She turns in her seat and faces the wall. A blush creeps up the side of her neck, and she fidgets with her hair.

Yeah, she remembers me. I chatted her up real good while my father signed my life away. She made things bearable. She can make things better than bearable. Just the warm, wet spot I need to forget about this horrid place for a bit.

My smile is back.

It’s a good day.

The door opens, and Headmaster Bridgeport enters. He holds the door for a big man with wide shoulders and a civil smile on his lips. A smile that I don’t buy. Not for one pence and not for one second.

There’s evil behind his gaze.

Now I’m the one swallowing. Gulping really. The hairs on the back of my neck go up. My pulse thrums in my stomach.

“Sit there.” The man’s fat index finger points toward me. I fight the urge to squirm, and I don’t fucking squirm for anyone. “I’ll speak with the headmaster.”

Threat coats the man’s words. No one else seems to pick up on it, though. Not the secretary. Not the young office workers in the back. Not the dumb-as-dirt headmaster. His dog, that ugly motherfucker, diverts from his master’s office to cower behind Miss Booth’s desk. The only smart one of the lot. He can sense the bad coming from that guy and gets the hell out of Dodge.

While the two men continue to the headmaster’s office, a guy materializes from behind the nightmarish man.

His spine is ramrod straight, and his chin is high. He looks strong and regal and also scared out of his fucking mind. No one else could probably tell, but I’m sneaky and stupidly good at reading people. It’s a gift…and a curse.

His eyes are intent on the man, hyper-focused, even as he sits with perfect posture. He releases a small bag gently on the floor. It’s a ratty duffel the size of a carry-on. There’s a wince as his ass meets the chair two away from mine. He favors his right side as though sporting an injury on his left. His hands are fists, and his jaw is screwed so tight it looks like he’s about to crack a molar.

The door closes, and the evil man disappears.

It’s as if the guy next to me takes his first breath of the entire day. It practically shakes the damn room. He blinks as though just taking in the world around him. He clocks the secretary first but doesn’t really see her and all she has to offer. Maybe he doesn’t yet know that she’s the only slice for miles.

Looks like he’ll learn soon enough.

This is for sure the new kid everyone’s buzzing about. He’s wearing a bespoke suit that’s two sizes too big for him instead of the school uniform.

If I’d seen him before, I’d remember.

His isn’t a face I’ll forget.

Author Bio:

Meg Everly writes stories with sentiment, smut, and love with no bounds.

Website / Goodreads / TikTok / Instagram / Booksirens

GIVEAWAY!

a Rafflecopter giveaway